University of Minnesota Press, 2021 Hardcover: 17.95

Reviewed by Pritika Pradhan

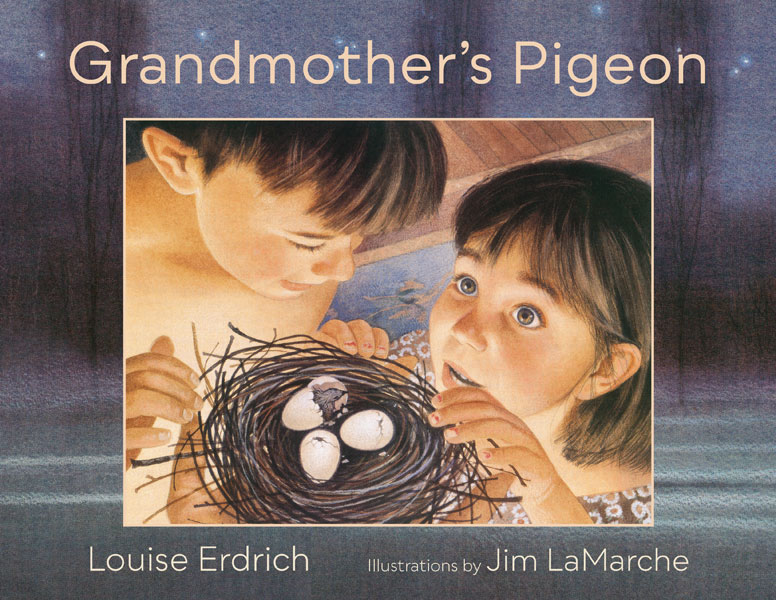

Louise Erdrich’s Grandmother’s Pigeon is a stunningly illustrated, wistfully whimsical parable of discovery and loss, extinction and rebirth, that embraces its contradictions instead of resolving them neatly. First published in 1996 and reprinted by the University of Minnesota Press in 2021, the story expands on a tale of familial loss to explore the extinction of nature, and the wonder of its unexpected regenerations, to be protected even at the cost of letting them go. Wonderfully illustrated by Jim LaMarche’s vivid acrylic and colored-pencil art, Grandmother’s Pigeon is a lyrical, heartwarming yet elusive tale for children and children at heart.

Grandmother’s Pigeon begins with the sudden departure of the titular Grandmother, narrated by her young granddaughter. Grandmother is a memorably intrepid woman, skiing the Continental Divide, training mules, and staring down vicious dogs, so it is hardly surprising when she hitches a ride on a porpoise to visit Greenland. Yet, after no contact for a year, the family is forced to accept she is gone forever. While sadly cleaning out her room, they find – amid the collection of birds’ nests and a single stuffed pigeon – three live eggs, which hatch to reveal long-extinct passenger pigeons. Erdrich delivers her most serious and straightforward message here, through an ornithologist: “nature is both tough and fragile. Greed destroyed [passenger pigeons].” Yet, for all its well-intentioned earnestness, the story is most effective when it mingles fancifulness and sincerity: seeking to protect the birds from imprisonment in the name of science, the narrator and her brother set the birds free, with messages pinned to their legs. They receive a reply from Grandmother in Greenland, promising to return soon.

This is a deceptively simple tale, memorably told; its charm and effectiveness come from its gentle irony, its gentle resistance to tying up its plot. The mystery of their appearance and final destination, and their connection to Grandmother, is not explained. Yet this open-endedness enhances rather than detracts from the story’s magic, as though gently inviting the reader to embrace its mysteriousness, without looking for neat solutions. Enhancing the story’s mysterious magic are LaMarche’s illustrations, which are at once extraordinarily detailed – capturing the birds’ feathering and their featherlike, intricate nests (one being made of spiderwebs) – while also being vividly expressive, conveying the nuances of the children’s wonder-struck expressions, and the inexplicable, self-satisfied smile of Grandmother’s stuffed pigeon. They complement the young narrator’s wonderstruck yet accepting voice by giving her story a warm, living reality, creating a startling and inhabitable experience for children of all ages.